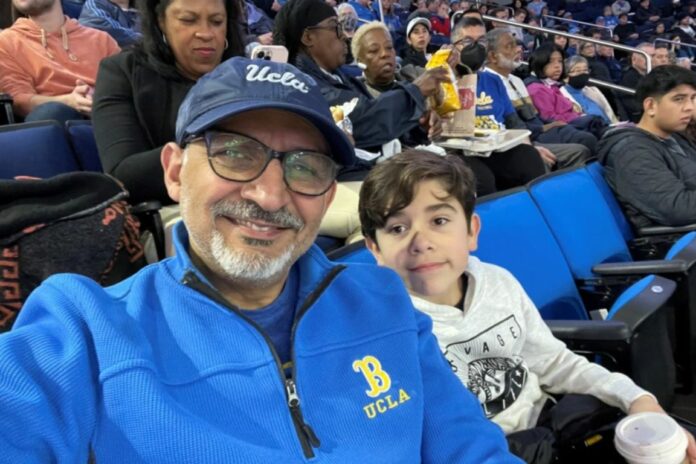

Ihab Shahawi found his passion at UCLA — helping people affected by autism

Some love stories are lifelong. Take, for instance, Ihab Shahawi and UCLA.

Born in Cairo, Egypt, and raised in New Jersey, Shahawi happened to catch an ad for UCLA during a college basketball game on TV at age 10. Dazzled, he vowed to his single father that’s where he’d go to college, distance be damned.

“He said, ‘That’s great,’ you know, just pacifying his son but being supportive, right? But then four years later, he came to Southern California for his best friend’s wedding and fell in love with the area — and a bridesmaid,” Shahawi said. “They got married, and we ended up moving. I was so excited that when the time came, I filled out only one college application — you can guess where — and sent it in myself.”

Not only was he admitted, but Shahawi immediately dove into his Bruin dream in the fall of 1979. In his first quarter, he joined the Theta Chi fraternity and made the varsity wrestling team; in his second, he realized how passionate he was about pursuing psychology. But it was a course in behavior modification with famed scientist Ivar Lovaas that would send Shahawi down his future professional path.

Getting the opportunity to join Lovaas’ lab as a senior, Shahawi spent a year working with children and families affected by autism spectrum disorders and quickly realized this was his passion. Although he couldn’t afford to go to graduate school, he discovered a new way in to the field thanks to a fraternity brother. This friend’s father happened to be clinical psychologist Gary LaVigna, who co-founded the Institute for Applied Behavior Analysis with his colleague Tom Willis, a former teaching assistant of Lovaas’. LaVigna and Willis’ innovative, non-aversive approach would transform lives around the globe.

Shahawi was offered a position as a direct care staff member in their first supported living home; within a few months he was promoted to a supervisor role tasked with growing the program. And he succeeded: In one year they went from three young adults in the program to almost 30.

After a few years working for LaVigna and Willis, Shahawi gained additional experience by leaving IABA with their blessing to work in a larger facility, overseeing more than 100 clients and 100 staff members. Then he made a bold decision.

“I decided it was time to open my own facility working with the most behaviorally challenging individuals with autism and intellectual or developmental disabilities,” he said. “I did some more research and found that the highest need was with teenagers, so I decided to focus on them.”

Shahawi’s first patients were four teenagers from the about-to-close Camarillo State Hospital. (Literally as Shahawi got the young men settled in the car, the staff locked and closed the facility for good behind them.) The eventful first day didn’t stop there. When Shahawi finally got them to their new assisted living home and began unloading the car, one of the teenagers, who had arranged to be met there, jumped out and got into a parked car and sped off.

“Before any of us even got in the house, we had already lost one, never to be seen again by us or the regional center. That was the bad news,” he said. “The good news: We were able to get the other three settled in and set up a program for them. It became successful and they were successful — each of them stayed with us until they either were able to move home with family or to another home with less support because they were all doing so well.”