The Secret Life of Albert S. Bard

While writing his 2008 book Preserving New York, Anthony Wood became intrigued by a key piece of legislation known as the Bard Act. Wood learned that the law was named for its author, Albert S. Bard, X 1888. Drilling down on his research, Wood went to look at Bard’s papers, that had been donated to the New York Public Library in the 1960s.

Nothing could have prepared him for the decades-long journey he was about to embark on.

“My expectations that first day at the library were extremely naïve,” he says, laughing. “There were more than 100 boxes of donated documents on Bard. It didn’t take long to see there was a lot more to him than preservation legislation.”

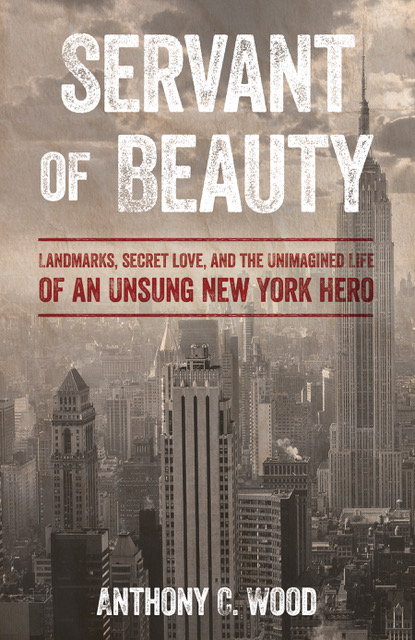

More than 20 years have elapsed since that day and Wood is finally sending his manuscript to the publisher. After perusing thousands of files and letters, requesting sensitive documents from the FBI and foreign intelligence agencies, and combing the Chi Psi archives, Servant of Beauty: Landmarks, Secret Love, and the Unimagined Life of an Unsung New York Hero is finished.

“It all began when I noticed references to an adopted son in the Bard files at the library,” says Wood. “By then, I had learned that Bard was considered a bachelor with no family, so I was intrigued by this discovery.”

Wood reached out to the donors who had gifted papers to the library more than 40 years prior. To his shock, he received a phone call on behalf of a then-90-year-old woman named Marjorie Switz Dunbar. She wanted to talk in person.

He traveled to meet Dunbar for an interview. When he arrived, Dunbar told him to turn on his tape recorder. Marjorie referenced a program about Bard that her daughter had attended. Someone approached her daughter at the reception and asked if her father, and Marjorie’s husband, had a romantic relationship with Bard.

“Marjorie volunteered the anecdote during our interview,” says Wood. “And she answered the question, saying, ‘And, of course, it was true.’”

***

Wood is not a Chi Psi. The former Adjunct Columbia University Associate Professor is an alumnus of Psi Upsilon Fraternity at Kenyon College. But you’ll forgive him for slipping up occasionally, and saying he is a Chi Psi in casual conversation. He spent more than 20 years chasing down every detail of a forgotten Chi Psi legend’s life, after all.

He first made contact with the Chi Psi Central Office to ask about Bard in 2003. Then-#23 and current Chief Advancement Officer Sam Bessey, HΔ ’97, responded to the inquiry and invited Wood to visit the Fraternity’s archives.

“Fittingly, when I first contacted Sam, he began his response by writing that he was sitting under a picture of Bard that hangs in the Central Office,” says Wood.

Bessey and #7 Bill Hattendorf, AΔ ’69, Σ ’81, H ’82, ZΔ ’23, have proved invaluable to Wood in his gathering of key pieces of history about Bard’s life. Hattendorf wrote in The Chi Psi Story (2022) that “Bard was the most distinguished interfraternity leader in the history of the Greek-letter movement,” and Wood’s research upholds that theory.

“Bard had three main pillars in his life,” says Wood. “One was Chi Psi. It was the longest commitment to anything he had in his life, and he remained active as an alumnus until he died at age 96.”

Bessey thinks Bard is one of the most under-discussed Chi Psi greats. Those with a deep knowledge of the Fraternity’s history know his name, but Bard does not appear as frequently in Chi Psi materials as many others. Some highlights of his civic life are detailed in The Chi Psi Story (2022), but they are only crumbs leading to the larger story.

Bard served as National President (#7), was one of the first three recipients of Chi Psi’s Distinguished Service Award in 1939, and co-founded the National Interfraternity Conference (NIC, now North American Interfraternity Conference; Bard also served as NIC President and played a pivotal role in Chi Psi Fraternity being a founding member of the Conference). He has the Fraternity’s Albert S. Bard Award – for contributions to enriching the intellectual and cultural life of the community – named in his honor. His Chi Psi resume is lengthy.

Luckily, Wood wrote Servant of Beauty, which is set to publish in the Spring of 2025 (and will be available on Amazon). It details the remarkable life of a man hopelessly devoted to his loved ones and causes he held dear. It also revolves around a secret romance, legislative triumphs, and a desperate mission to rescue two spies in Paris.

The highlights are jaw-dropping, but Wood believes it was ultimately Bard’s incredible generosity and eternal commitment to the people and organizations he loved that should lead his legacy.

***

The Bard Act, as it became known, was the lasting civics legacy of a man who wouldn’t quit.

“He was like a dog with a bone,” says Wood. “He initially floated the concept behind the ordinance in 1913. Due to his unceasing advocacy, it finally became law in 1956.”

The fine print of the Bard Act essentially says that New York City has the legal authority to regulate on aesthetic grounds. And in the early 1900s, Bard’s love of civic beauty was being challenged by gaudy advertising – huge billboards, excessive signage, etc. – popping up all around New York City. His work led to the New York City Landmarks Law of 1965.

“Bard was so tenacious,” says Wood. “His thinking was decades ahead of most people.”

Robert Moses, the ultra-powerful urban designer in New York City at that time, faced opposition from Bard and other civic leaders. Bard successfully organized opposition to the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge project and helped preserve Castle Clinton, both slated for development by Moses.

“Bard is one of four civic leaders who took on Moses successfully twice,” says Wood. “He did so at great personal risk and it became something he was known for. Meanwhile, in his private life, Bard was totally consumed with and passionately committed to Gordon Switz, his ‘adopted son.’”

***

Here is where Bard’s story hits top speed, veering in and out of unbelievable dramas across two continents. According to Wood, around the time of the 1921 Chi Psi Annual Convention, Bard met a young Brother named Ted Switz (BΔ 1922). He became close with Ted, his two brothers, and their widowed mother.

“Ted’s brother, Gordon, became the emotional focus of Bard’s life for 26 years, from the time they met until Gordon died in 1951,” says Wood. “Bard became the de facto leader of the Switz family and took Gordon under his wing.”

Dunbar, the wife of Gordon Switz who replied to Wood’s inquiry, had known Bard since she was five years old. Her mother managed the house in which Bard had his private rooms. Dunbar met Gordon when he visited Bard, but the two re-connected many years later when she returned from studying at Vassar College.

“Gordon was troubled with behavioral issues,” says Wood. “And Bard was a millionaire at this time, so he sent Gordon to Paris to study, offered him flying lessons, and more. Then, the stock market crashed.”

The Great Depression of 1929 severely depleted Bard’s financial resources. But Wood says Bard’s generosity never wavered. In fact, he became even more giving.

“In 1933, Bard blessed the wedding of Marjorie and Gordon, despite his own personal relationship with Gordon,” says Wood. “They got married, went to Europe, and were promptly arrested. They were accused of being Soviet spies and charged as such. As it turned out, the accusations were true.”

Take a moment to remember the time frame; in the early 1930s, everyone was questioning capitalism and the Soviet Union was still an unknown experiment. Gordon was a young, adventurous guy and ended up connecting with a ring of Soviet spies after an introduction from his brother, Ted.

Their arrest was an international scandal. It made front page news in the New York papers and was covered in England and France. Both of Gordon’s brothers lost their jobs in the U.S. as a result, disgraced by his and Marjorie’s actions.

According to The Honeymoon Spies by William T. Murphy, Gordon and Marjorie were appalled by “poverty, unemployment, and chaos” all around them, which led to their belief that Soviet-style socialism was the cure to the world’s problems. Described by Murphy as affluent, well-educated, and attractive, Gordon and Marjorie began training as Soviet spies in New York before their ill-fated trip to Paris.

There, the story goes, Gordon began doubting their handlers’ motivations and challenged them, threatening to quit. Gordon became increasingly nervous with the situation and detected French security officials following them. So, he was unsurprised when the couple was arrested. According to Murphy, Gordon and Marjorie were the first Americans to be arrested as spies in France.

“Despite his greatly diminished fortunes, Bard was the titular head of the Switz family and Gordon was the love of his life,” says Wood. “He hired lawyers, flew to Paris, and helped navigate the situation. Eventually, Gordon and Marjorie turned on the Soviets.”

Upon returning from the crisis in Paris, Bard whisked Gordon and Marjorie to a remote cabin in upstate New York (originally built by another Chi Psi, Louis Huthsteiner, X 1914), to stay off the grid in the face of tremendous backlash.

***

In a way, what Bard was doing for the Switz was like leading a secret life. While becoming an unsung hero of the civics movement in New York City and expertly representing Chi Psi and the many other organizations he belonged to, Bard was privately managing hugely complex political situations involving his secret lover.

“Many people don’t realize the impact Bard had on New York City due to his landmark preservation work,” says Wood. “And most of his Chi Psi world – which was the majority of his trusted social network – has no idea what was going on in his personal life. Those in the civics industry certainly had no idea.”

While fighting to enshrine the Bard Act and traveling to Chi Psi Conventions, Bard was also going to Washington, D.C. to keep Gordon from testifying in front of Congress. He was meeting at the White House. He was using his personal connections to make back-door pleas to friendly Supreme Court Justices to expedite travel documents for Gordon and Marjorie.

Wood has a theory as to why Bard advocated so tirelessly – and gave so endlessly – to the people and things he loved.

“Bard was three years old when his mother died,” says Wood. “By the time his father remarried three years later, two of Bard’s brothers died from influenza. He had so many disruptions to the family dynamic in early life, I think there’s a reason he became so devoted to his people and his structured organizations like Chi Psi.”

When Gordon had medical problems, Bard sent him to the Mayo Clinic. When Gordon succumbed to his illnesses and Marjorie eventually remarried, Bard stayed close and continued in his role as de facto grandfather to her four kids.

“Bard was just a totally resilient and hugely generous person, even after he lost all his money in the Great Depression,” says Wood. “When Gordon got a job as a day laborer in upstate New York, he told Bard of a friend trying to get a work transfer closer to his sick wife, so Bard wrote a letter to get him transferred. Bard’s private life is an endless list of good deeds.”

***

In that era, homosexuality was, of course, not socially accepted (nor legal). Bard kept his relationship with Gordon a secret outside of his tightest inner circle, for obvious reasons. In the course of his research, Wood began to wonder how Chi Psi would receive the newly revealed chapters of Bard’s life.

“Chi Psi has been very, very open and welcoming to that from the get-go,” he says. “I’ve learned that there are other prominent gay Chi Psis, but I was a little worried at first how this discovery would be taken. Thankfully, it has never been an issue.”

When it comes to a Brother like Albert S. Bard, who gave so much time, energy, dedication, and defense to Chi Psi, “excellence” becomes an understatement and his sexual orientation becomes even less relevant.

“If Gordon was the emotional center of Bard’s life, Chi Psi was the social center,” says Wood. “In the archives, there are pages and pages of documentation about Bard visiting his Chi Psi Brothers across the world, being involved in the design of Alpha Chi’s Lodge at Amherst, his activities as an alumnus.”

***

Wood’s book is set to be released in April 2025, which happens to be the 60th anniversary of New York City’s Landmarks Law that wouldn’t exist without Bard and the Act that bears his name. The book includes a section devoted to Philip Spencer, too, because Wood thinks Bard might have recognized similarities between Spencer and Gordon.

“I think Bard definitely saw one in the other,” says Wood. “Gordon went off sailing when he was a young man. Both had physical limitations and relentless adventurous streaks. And we know Bard was deeply devoted to Gordon, like he was devoted to Chi Psi, which Spencer is the central figure of.”

Given Bard’s connection to Chi Psi and the timeframe of his relationship with Gordon, Wood also thinks Herman Melville’s Billy Budd – believed by many to be based on the hanging of Philip Spencer – may also have influenced him.

Whether Bard saw those parallels or not, we’ll never know. We do know, thanks to Wood’s painstaking research, that Bard was unmovable in his love for Gordon, just as he was in his support of Chi Psi.

Though their situation was unique, Gordon and Marjorie were clearly fond of Bard.

“Marjorie was the one who went through stacks of Bard’s files when he died and made sure not only to donate them but to categorize each and every one so the right organization received the proper documents,” says Wood. “She made sure the Chi Psi files went to Chi Psi, and so on.”

But it wasn’t just that Marjorie managed Bard’s affairs after his death. Marjorie and Gordon loved Bard as he loved them. When they had their first son in 1938, they gave him a special name: Albert Bard Switz.

###

Related: “A Dog with a Bone.” New Wood Book Reveals Bard’s Secret Passion

By Adrian Untermyer, Archive Project Board Member