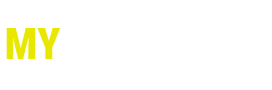

Stacy Bare, Chi Psi, National Geographic Adventurer of the Year in 2014, and 2015 SHIFT Conservation Athlete of the Year, is a climber, rugby player, and skier. He is a veteran of the Iraq war, and he’s served as Director of Sierra Club Outdoors (SCO), getting 250,000+ people outside each year. Stacy co-founded the Great Outdoors Lab in 2014 to put scientifically defensible data behind the idea of time outside as healthcare at the Greater Good Science Center at UC-Berkeley. He’s a brand ambassador for The North Face and Combat Flip Flops. He holds degrees from the Universities of Mississippi and Pennsylvania and is at home in Salt Lake City with his wife, Makenzie, and daughter, Wilder. His favorite thing to do in the outdoors is tied between skiing and dog sledding. In 2017 he and two fellow veterans completed a first ski descent of Mt. Halgurd in Iraq. He talked with us recently about his life since his Army service:

In the Army, I knew what I was doing with my life. That had been the dream – since I was five years old. And I’d gone from that to ROTC, to active duty, and then I did land mine clearance, which really felt like the Army in a lot of ways, and then I was back in Baghdad, and then I went to graduate school, so I knew who I was. And then I don’t know who I am anymore.

In the Army, I knew what I was doing with my life. That had been the dream – since I was five years old. And I’d gone from that to ROTC, to active duty, and then I did land mine clearance, which really felt like the Army in a lot of ways, and then I was back in Baghdad, and then I went to graduate school, so I knew who I was. And then I don’t know who I am anymore.

I wanted to forget, I wanted to be somebody else, I wanted to move on, so I was just trying to make up for lost time. I was so nervous about becoming a statistic, about becoming a veteran, and to me I guess that meant being a drug addict, an alcoholic, being unemployed, meeting the VA (I thought I didn’t need help; I didn’t want help).

You know, I didn’t see myself as having an addiction. I didn’t see myself as having a problem with drugs or alcohol. I didn’t see myself as being angry. I saw other people as having a problem not understanding how to live life to the fullest. I would get high and then try and run through a wall, and that was a fun party trick for me.

Stacy did tours in Sarajevo and Iraq in the U.S. Army as a Captain, and never doubted he would serve. His uncle was a Green Beret in Vietnam, and his grandfather, a Seabee in WWII. Raised in eastern South Dakota, Stacy spent his childhood exploring Western and Midwestern landscapes, and early on learned the value of service in his small town, since “everyone had to pitch in.”

There was no such thing as a single-sport or single-athlete kid. Everybody did a little bit of everything, and Stacy credits his willingness to try new things to that mentality.

Bare graduated ROTC from Ole Miss in 2000, and was stationed in Germany. He deployed to Sarajevo for six months from 2003-04. After his tour, he worked clearing mines in Angola and Georgia with the humanitarian organization The HALO Trust until 2006, when he was recalled to Iraq.

I don’t think you can necessarily point to a time where I said, “Well, here’s where you’re breaking, here’s where you lose it.” I wanted to know who I was, or if I couldn’t answer that question, I wanted to cease being. I didn’t think about it as committing suicide, I thought about it as just “ceasing being.”

I think the hardest part when you get out of the military is all of sudden, it’s like, “Where do I go? What do I do?” The fact that you can do almost whatever you want can be really scary and overwhelming.

Because I’m a big tough veteran and I’m a big tough guy, I was like, “Nothing’s wrong with me, there’s something wrong with everybody else, not me.”

I knew I needed to get outdoors and give myself some time to rebuild and heal, so immediately after returning from Iraq I took off on a multi-week surfing expedition to South Africa. It was my first time ever surfing and I spent most of my time falling. Looking back, I think getting wrecked by those waves alone in the water was what I needed to get me through the next two years of my life. But shortly after that trip, I was still a mess. While attending graduate school, I was torn between wanting to descend into a total absence of feeling and a desire to “be productive.” I needlessly hurt people and still have some shame around my actions those first few years home.

With a sluggish economy, I couldn’t find a gig in urban design after finishing my degree. So I ended up in Boulder. One of the guys I deployed with was a contractor but he was a retired special forces guy; he asked me to put off killing myself for a week or two and come rock climbing with him, phrasing it as, “Let’s have an adventure,” not, “Let’s go out to heal.” And I thought, “Yeah, I can wait a couple weeks before reenlisting or killing myself. I’ll go climb with him and see how it goes.” …

So I did … And it changed my life!

. . .he asked me to put off killing myself for a week or two and come rock climbing with him, phrasing it as, “Let’s have an adventure,” not, “Let’s go out to heal.” And I thought, “Yeah, I can wait a couple weeks before reenlisting or killing myself. I’ll go climb with him and see how it goes.”

Stacy describes what he saw during his year-long deployment in Iraq as very “middle of the pack” in terms of tragedy. When he returned home, he didn’t think he should be hurting, because he hadn’t seen it “bad enough” [a classic reaction of many veterans no matter how tough the service]. Being in a war zone can mean a near-constant rush of adrenaline that vets often really miss whan they return home. Trying to reintegrate into civilian life was a real struggle for Stacy, battling depression as well as substance abuse.

The sense of purpose I felt serving alongside my fellow soldiers was addictive. Life, distilled daily into decisions that would either get you killed or not, was strangely simple and liberating. The key was not to think too much.

While working in Baghdad, I got to know many of the locals on a deeply personal level, and I heard stories of summer vacations to the snowcapped mountains in the north. On patrol in full body armor, baking under the hot Iraqi sun, I daydreamed about hiking those peaks, cooling off in the snowfields. I never saw the mountains during my tour, and when I left the country, in 2007, I never imagined I’d go back.

Clutching onto a rock face, hanging by a rope, I was a novice again. I was experiencing new challenges that necessitated vulnerability. As a six-foot-seven male, I was not accustomed to asking for help.

Through time outside, though, I realized that it was OK to ask for help, and it was OK to go to the doctor, and it is OK to be frustrated, to be angry.

I discovered that adventure outside replicated positive attributes of military service, like camaraderie, perseverance and leadership skills. It also presented me a fresh opportunity to form an identity beyond the military.

In 2010, Bare and fellow veteran Nick Watson founded Veterans Expeditions (VetEx), a Colorado-based nonprofit that seeks to address the unique struggles and needs of veterans through time outside, on expeditions led by other veterans. The following year, he accepted a job at Sierra Club Outdoors as the Military and Veterans Affairs Coordinator. By 2012, he was Director of all of Sierra Club Outdoors, providing over 250,000 individual outing opportunities in the U.S. every year.

I view the ability for the outdoors to heal trauma, and trauma itself, to be universal. How we got our trauma and why we suffer might be unique and oftentimes is, and that deserves some special attention. But that we suffer and that we have trauma … Those are not unique.”

The outdoors offers a pathway towards creating a new identity in the aftermath of trauma. One of the things we looked to do when we’d take people out is to build onto identity, to help individuals shape it how they choose to shape it. To tell their story how they choose to tell it. Not to have somebody else dictate to them their story, and how that story is going to end.

The outdoors offers a pathway towards creating a new identity in the aftermath of trauma. One of the things we looked to do when we’d take people out is to build onto identity, to help individuals shape it how they choose to shape it. To tell their story how they choose to tell it. Not to have somebody else dictate to them their story, and how that story is going to end.

I’ve studied how time outside could be integrated into traditional prescriptive medicine and am working to create more robust research around the healing power of nature. The San Diego VA recently started prescribing surfing. How do we get every VA, every hospital, every insurance system, prescribing time outside?

Time outside can heal not only individual wounds but collective as well. In an age of divisiveness, nature creates commonality between people of disparate backgrounds and beliefs, in part because the forces of nature don’t discriminate – the same rain falls on all shoulders. When people sit around a campfire after a rigorous day outdoors, they are much more interested in figuring out their common humanity than their differences. I’d love to get all five-hundred-plus members of Congress out on trips.

Right now, when we’re stuck behind screens and we’re stuck in boxes and we’re stuck in offices, it’s a lot easier to read something and yell back at it, or write an e-mail and press send and let it make its ripples. A lot of veterans feel isolated, but gosh, a lot of people feel isolated. If we could just find a way to help each other out a little bit in the real world, face to face, analog … We’d be doing a lot better.

In this vein, I began to wonder if the outdoors could also build bridges across cultural and global divides. When I first re-entered civilian life and began to share my story of service, a lot of the time, people would respond very negatively about a country and the people in a country, like Iraq for example.

My own experience with locals from those countries had been just the opposite. I began to ask: “What can I do as a service member, as a veteran, to help share a different story to people?” as well as the question, “What can I do to, somewhat selfishly, find peace?” I wondered what it would look like to return to the countries where I had served, whether at war or after war, to ski and climb. Maybe, I thought, I could create a new narrative for myself and for others, with those places and people, centered around the landscape and adventure.

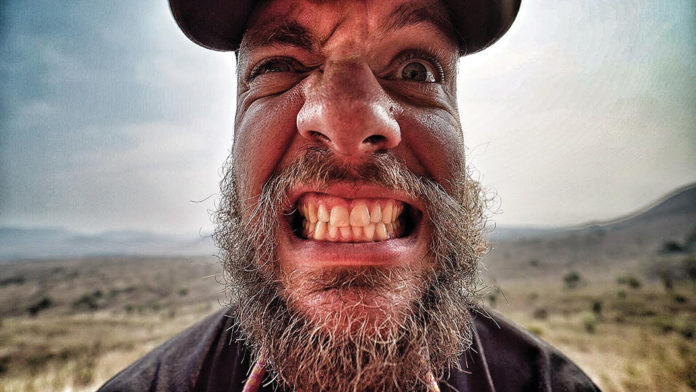

Out of this questioning came the multi-country, multi-year initiative, Adventure Not War. As part of ANW, I returned to climb in Angola in 2015 with professional rock climber Alex Honnold and Vice Sports. In 2016, I traveled with two U.S. veterans to make a winter ski ascent of Mt. Halgurd, the second-highest mountain in Iraq, documented in a film by The North Face.

I wanted to make sure I rewrote a different ending for myself in Iraq. The film presents Iraqi culture and people alongside expeditionary components.

I feel like I have a responsibility to go back and explore the places and people that maybe I’d heard about and seen glimpses of when I was over in these countries like Iraq the first time. I’d heard about skiing in northern Iraq and Kurdistan. Mt. Halgurd was the main objective, and as far as I know, nobody had ever skied up and down.

I invited friends of mine that I think have really powerful stories and are doing really amazing things in the world. Robin Brown owns her own PR firm, the mother of two. She was serving in 2003 as a pilot; she got shot down over Kaluzia. Griff (Matthew Griffin) fought in Mozul as part of the U.S. Army Rangers, and I knew that he would be rock-solid for this trip.

Robin: “So when Stacy called me to see if I wanted to go make a ski movie about Iraq, my first reaction was ‘No’ because never in a million years would I want to come back to Iraq. I’m a pilot, and so I saw this country during my first two deployments from 200 to 300 feet up. I had almost no interaction with the people. And then at the end of our mission we’d go back to our airfield surrounded by a wall.

“I didn’t really understand the history of the country, I didn’t know the people, I didn’t understand the difference between Shia or Suni or Kurd and so everything about the environment scared me.

But Stacy is one of the funniest people I have ever met. He’s even funny looking. He’s a giant of a person, and everything that comes out of his mouth is very funny.”

Matthew: “They say people do things out of two major emotions: One is love and one is fear. And I think we’ve been exposed to the fear-based lifestyle for years now. We’ve invaded foreign countries and caused war; we’ve lost our soldiers, we’ve caused collateral damage, resulting in major degradation to U.S. foreign policy abroad, and it’s all been based on fear. We’re scared of something happening to us. Instead, when we go out into a foreign country, we could create a relationship with people, do something positive, and actually build a connection. That might inspire others to do the same.

The last time I was there (Mt. Halgurd) was about 12 years ago and I saw most of the country under the hours of darkness filled with so many deaths, and that’s one of the things I’ve had to come to grips with over the last ten years. I may never know why I went to Iraq; I may never know why I got to live and Brian Freeman didn’t; but the key thing is that at some point I have to start living again.

How many wars can we avoid entirely, because we’ve also built up these bridges of cultural understanding?

When getting to the base of the mountain, surveying the best routes up and down, we realized that some of what might be the best ski areas we’d have to avoid because of remaining land mines. As Stacy said, “You won’t get your pass pulled, but you might lose a leg.”

I had to take care of my own healing process. We all have to take care of our own healing process, ultimately. That’s why I wanted to go back. I wanted to make sure that I had a different ending for myself in Iraq.

After much mountain skiing/hiking, we put our skis on our backs, put our crampons on, and climbed what I felt was pretty extreme climbing like I had never done before. It was physically hard, but more than anything it was scary, because every time I turned around and looked down, it was a long way down. I remember thinking part of me didn’t want to do it, I was just too scared.

Stacy shared a quote from René Daumal:

“You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know.”

Then Stacy said: I can’t unsee my war, but I will always know what it was like to be both at the highest point in my life, both literally and physically, in Iraq, as well as at the lowest point in my life, in Iraq. And I think that the only two things that are more powerful that I can remember than climbing in Iraq are the birth of my daughter and meeting my wife.

There’s a tremendous amount of beauty that’s being masked by this war. If we can focus on that beauty, how many wars might we avoid entirely because we’ve also built up these bridges of cultural understanding through things like late-night dancing in a mountain hut after a long day of chasing powder? I met a man who was a member of the peshmerga for 40 years, who said, “I’ve climbed Halgurd dozens of times, a hundred times, but now I’m too old to do it, so I just go out and look in my binoculars and see the top and remember what it was like to be up there.” Now he and I have something more in common: We’re not just warriors; we’re mountain lovers, we love being outside. And we can share that too. And like he said, ‘That’s how we’re going to get to peace.’

And he’s right.

All three of you for the Mt. Halgurd were Army Captains. Was it a relationship in the service that brought you three together?

No, actually, We actually all know each other through the outdoor industry and a very informal network of veterans. That we were all three Army Captains is pretty happenstance. I met Griff at an outdoor retailer event in 2012 with a short film. I met Robin in Colorado, where I was speaking at the Colorado Outdoor Industry Leadership Summit. She had signed up for a ski trip I was running through the Sierra Club, so it just came together. None of us thought, “We’re three Army Captains.” It was more, “We’re three veterans who are skiers and we all want to go back to Iraq.”

You mention two highest points in your life as being when your daughter was born and meeting your wife. How did the two of you meet, and at what point were you in your recovery journey?

I met Makenzie looking for an apartment in Boulder and she had a room to rent in the house she was living in. Friends told me I had to be funny in responding to Craigs-list ads if I wanted to have the writer respond, so I was funny and she wrote back. We actually just emailed for quite some time and when I moved to Boulder (and not into her house), I asked her if I could meet her for a drink. I freaked out a few months later, stopped talking to her, but then reached back out and well, you know the rest!

As far as where I was in my recovery journey, I didn’t get sober until 2011 and we met in 2009. I think I was also just really beginning to understand what it meant to have the feelings I had been feeling for a couple of years and that they might have big, scary names like depression, PTSD, etc. Shortly after we met I started climbing and pushing myself in adventure in a way neither of us likely saw coming. So, she’s been incredibly patient, kind, supportive, and also someone I really look up to, admire, and try and emulate in a lot of ways. She has a tremendous amount of grit, is by nature very laid back and calm, and is really great at being present in a way I struggle with. My mind is going 100 places at once – she’s pretty focused on the here and now. It’s amazing. She’s also incredibly intelligent, she has her Ph.D., and her mind works in a way that is fascinating to watch. She’s a great writer.

Tell us something about your time as an undergraduate Chi Psi and being #1 at Alpha Gamma.

My four years as an undergraduate Chi Psi were great. All in all, it was phenomenal. But as an undergraduate, I had no idea how much a role the organization and my Brothers would play in the years down the road. There were negatives, of course, and fraternity men haven’t always done the right thing.

When I was about to be deployed to Iraq, we had a last-night farewell party. Several other people had friends or family members join them, and I had a Fraternity Brother drive hundreds of miles to be there for me too. Other folks kept asking who this was, and why would a guy drive so far with no closer relationship than a college fraternity? They couldn’t understand the strength of the bonds we had.

But we believed the stuff they told us in initiation. Chi Psi is all about close, elevated friendship, for all our lives. I think the genius of Chi Psi and of what Philip Spencer and his fellow founders (perhaps even unintentionally) set out to be was that we were to be gentlemen. Those values, which we as a fraternity have succeeded and failed at upholding in different levels throughout the years, are pretty timeless.

Can you be a gentleman and a liberal? Yes. Can you be a gentleman and a Republican? Yes. A gentleman and gay? Yes. A gentleman and of Mexican or African descent? Yes.

We’ve made some mistakes at some of our Alphas, but we always seem to come back, because we know we can do better.

With all the things I’ve been involved in, the Brothers in Chi Psi have continued to show up and support me. The #23, Sam Bessey, is a great example. He has reached out to me so often, and when he does so, it means so much. He’s a great cheerleader for Chi Psi and such a great Brother to so many of us individual Brothers.

But what’s manlier than standing up for those who have traditionally been downtrodden or attacked? What’s manlier than working with those individuals or communities to feel strong and empowered?

From when you were in college until now, the world has changed enormously. Twenty years ago there was no #MeToo movement, there was practically no talk of misogyny or white privilege. It may be that the attitudes of the late ’90s weren’t all that different from those of the late ’60s, but today it’s a whole new world. And it can be confusing for people growing up in this changing world, as well as for those of us witnessing the change. Any thoughts on what we can do to help our young men deal with all this? Is it possible to be “a man” in the middle of all this? Is it possible to be a “real man” and still be allies with the other sex?

What a great question! I think there is certainly a different understanding of masculinity today than there was even when I went to college, and I think a lot of people are very frightened, for understandable reasons, about what this change means.

What concerns me is that a lot of people see a subtraction of who or what they are when we talk about #MeToo, white privilege, or tackling misogyny.

But what’s manlier than standing up for those who have traditionally been downtrodden or attacked?

What’s manlier than working with those individuals or communities to feel strong and empowered?

What’s manlier than having honest discussions about race and working to acknowledge your own internal biases and actions that may have harmed others? I know that at times even our own Fraternity Brothers have denied brotherhood to men of exceptional character because they were black, brown, or gay.

I think that the Fraternity as it was originally conceived in its high ideals can have cultural relevance today more than ever before, that the idea of a Chi Psi Gentlemen is of paramount importance. We can and we should lead in not so much redefining what it is to be a man, but in living up to our timeless ideals and interpreting them in a way that brings strength to the entire community. We won’t stand any taller because we’re forcing others under.

We must be willing to acknowledge our mistakes, seek criticism and healthy debate, and be willing to grow stronger because of it.