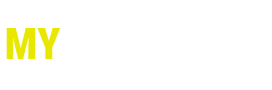

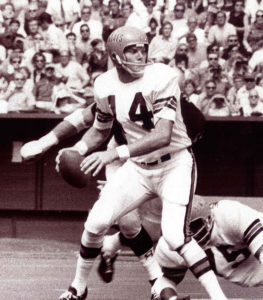

Sam Wyche, Kappa Alpha Order (Furman ’66), is one of the ultimate innovators in professional football and has a winding pedigree in the sport. Wyche walked on as quarterback of the Furman Paladins. Upon graduation he was initiated into Kappa Alpha Order, married his KA rose Jane, and then drove south to obtain his Masters of Business Administration from the University of South Carolina.

Sam Wyche, Kappa Alpha Order (Furman ’66), is one of the ultimate innovators in professional football and has a winding pedigree in the sport. Wyche walked on as quarterback of the Furman Paladins. Upon graduation he was initiated into Kappa Alpha Order, married his KA rose Jane, and then drove south to obtain his Masters of Business Administration from the University of South Carolina.

There, he began a graduate assistantship under Lou Holtz. Somehow he managed to also play for the Wheeling Ironmen of Wheeling, West Virginia, in the then nascent Continental Football League. He played professionally for several years in the CFL, AFL, and eventually the NFL. He was the quarterbacks coach for Joe Montana and was a member of that staff during their Super Bowl XVI championship. The 49ers Head Coach, Bill Walsh, was proliferating the new “West Coast Offense” with Wyche and Montana—a scheme he developed while Walsh was assistant coach and Wyche was quarterback, together at the Cincinnati Bengals. Wyche returned as Head Coach of the Bengals, in 1984. He introduced the “No Huddle/Hurry Up” offense that is utilized today by every NFL team. His 64 wins with the Bengals were the most by a coach in franchise history until 2011, when that record was surpassed. He continued coaching at Tampa Bay, Buffalo, and eventually for Pickens High School, in South Carolina, as a volunteer. He made numerous friends and very few enemies (just Google “Glanville and Wyche”), and became a respected announcer in the 2000s on NBC, CBS,and Fox Sports South.

It turned out that his heart function was greatly reduced by the effects of the long-term and rare viral infection. There was then, and now remains, no cure.

Sometime in the decade before the year 2000, a virus silently entered Sam Wyche’s body and began slowly attacking his heart. He felt nothing amiss and wasn’t ill. Bit by bit, his heart muscle lost strength and endurance. Exercise was always part of Wyche’s daily routine, but the disease process was so slow that if he felt less resilient or lost endurance, he wasn’t conscious of it. If he noticed anything at all, he probably just chalked it up to getting older.

In March 2000, after a Bear’s broadcasting gig at Soldier Field, Wyche felt an overwhelming fatigue and pain in his chest. It turned out that his heart function was greatly reduced by the effects of the long-term and rare viral infection. There was then, and now remains, no cure.

The combined effects of the progressive disease and advancing age sentenced Wyche to a premature death. A pacemaker, a Greenfield filter, and other miracles of modern medicine extended his life and allowed him to play golf, work around the ranch, and travel the country speaking to business, religious, and other groups. Other than giving up flying, Wyche lived a pretty normal life and could carry on with the disease having minimal effects. One doctor wanted to do a biopsy of Wyche’s lymph nodes to see if lymphoma cancer could be the answer to the heart problem. To add insult to injury, in the process of the biopsy the doctor severed Wyche’s laryngeal nerve when he cut between the wrong ribs in his chest. The severed nerve rarely heals itself, and this one did not. After three surgeries to place a stint behind the affected vocal cord, Wyche began to be able to talk normally again. In addition, Wyche had a number of pacemakers and defibrillators installed and replaced with new models. He did not change his lifestyle or daily routines for many years.

The combined effects of the progressive disease and advancing age sentenced Wyche to a premature death. A pacemaker, a Greenfield filter, and other miracles of modern medicine extended his life and allowed him to play golf, work around the ranch, and travel the country speaking to business, religious, and other groups. Other than giving up flying, Wyche lived a pretty normal life and could carry on with the disease having minimal effects. One doctor wanted to do a biopsy of Wyche’s lymph nodes to see if lymphoma cancer could be the answer to the heart problem. To add insult to injury, in the process of the biopsy the doctor severed Wyche’s laryngeal nerve when he cut between the wrong ribs in his chest. The severed nerve rarely heals itself, and this one did not. After three surgeries to place a stint behind the affected vocal cord, Wyche began to be able to talk normally again. In addition, Wyche had a number of pacemakers and defibrillators installed and replaced with new models. He did not change his lifestyle or daily routines for many years.

The Red Zone

By 2015, however, things were going rapidly downhill. Feelings of general weakness and shortness of breath became more and more frequent for Wyche. Sleep was difficult, and his digestion suffered. It was nature’s way of slowing Wyche down and sending a message that his remaining time on earth was getting short. He would soon learn just how short it was.

When symptom care no longer worked, Wyche’s medical team recommended an implanted device called a Left Ventricular Device, or LVAD. Essentially, it’s a big complex battery-operated cardiac pump that helps a weak heart muscle push blood out to the rest of the body. One of the top surgeons in the country implants these machines in Charlotte, North Carolina. Wyche went to Charlotte for tests and an evaluation, and, to install the LVAD.

More tests and prep work for the LVAD showed a worsening in Wyche’s condition. He watched the doctors as they conferred among themselves. Something in their body language made him uneasy. Wyche wasn’t too surprised when a physician (dubbed “Doctor Doom” by the Super Bowl Coach) gently told him that for medical reasons he’d slipped past the window for an LVAD.

To their surprise, Wyche believes, the news didn’t trouble him at all. The cumbersome device just didn’t appeal. Installing and carrying around batteries, hoses, pumps, and paraphernalia for only the promise of a year or two of life extension just wasn’t worth it. Wyche was pretty sure he knew what God’s plan was, and it didn’t include the LVAD.

Two options remained. First, go home and enter hospice, receive comfort care, and wait for death. The other was a heart transplant. Wyche has stated, “I didn’t particularly care where I died, so I’d just as soon wait for a heart as long as I could in the hospital.”

The wait began, and Wyche remained at the Carolina’s Medical Center in Charlotte. He had mixed feelings about a transplant. To Wyche it seemed wrong to deprive anyone of a lifegiving organ, and especially so given that at his age he, “was within hailing distance of the pearly gates anyway.” As he prepared for death he was comforted by his faith. “I was saved by God’s grace and eternity in heaven sounded pretty good to me.”

His condition spiraled downward, and he reached a point where he was rated 1-A for a transplant. “It was probably the highest I’ve ever been rated at anything,” Wyche jokes. It just meant that he was in the top level of priority for a new heart. In other words, there were no more timeouts for Coach Sam Wyche.

“I had no more than two to five days to live.”

He was in a race against time with three opponents. The first was the rapidly failing heart. The second was the terrible damage inflicted on his kidneys by the anti-rejection drugs he was required to take. The effects of long-term use of those drugs would be kidney failure. The third was time itself—waiting for a suitable heart that might not arrive soon enough.

Wyche summed up his final play, “When waiting is the only option, a sense of passivity controls your thoughts. All my life I’ve acted upon adversity, opportunity, good-fortune, crisis, and all manner of challenges, both personal and professional. This was something new. My fate was entirely outside my control, an unfamiliar feeling in itself.”

Every day brought the same news: No hearts with Wyche’s requirements were on offer. A larger geographic net, now encompassing the entire Midwest, was cast to find one. The famous Cleveland Clinic was put in charge of the search. “Given my past insults to that city in front of tens of thousands of football fans and a national television audience, the irony of the situation was not lost on me,” Wyche recalls.

All of the young men that attend our programs have always known professional football with a “hurry up” or “no huddle” offense, something Sam is credited with starting and proliferating in the NFL.

“No heart on Monday,” said Wyche. “No heart on Tuesday and Wednesday and eventually, Friday is the 5th day and still no heart.” Wyche asked doctors to extend the wait until the weekend and give it a chance. Saturday no heart. Sunday no heart. On Monday, September 12, 2016, the doctor came in and told Wyche that he still had no heart and that he had hours, possibly minutes to live.

“It was almost time to send me home, I mean the final home,” Sam said. The plan was to be discharged and have a PICC line, a percutaneous inserted central catheter, installed to administer medications. Hospice would be called in to assist at home for whatever time was necessary. The doctor told Wyche, “On the way home, we want you to call your loved ones, and say goodbye, because you’re not going to live through the night. Your heart is at the very end of its life.”

At this time, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Wyche’s son had just finished a high school football practice. Across town, Wyche’s grandson Sammy was the quarterback of another local team and had also just finished practice.

Around that same time, 5 pm or so, both Wyche’s son and grandson called their respective teams together at the end of their practices in a huddle to pray for their Dad and Grandfather. Praying for Wyche somehow, someway, to survive.

Back in Charlotte, almost 500 miles away from Cincinnati, that same doctor who had broken the grave news to Sam just hours earlier walked back into Sam Wyche’s hospital room again around 5 pm. This time, he had a smile on his face.

Sam remembered, “The doctor came in and told me it was a miracle. This is like a one in a million chance. The doctor found a heart with a person my size and told me once it arrived, that within hours, we were going to get surgery done.”

A family that may forever remain anonymous lost a loved one … a man who saw beyond his own earthly existence and offered his precious God-given corneas, heart, ligaments, kidneys, liver, and other organs to a group of equally anonymous people who would live after him. Other people he never met, and perhaps even children, would become the beneficiaries of the tragedy of his death. A mixture of emotions flowed over me. The hope of additional years of life and the relief of knowing I had a chance for renewed health and vitality, did battle with my empathy for the family.

Overtime

The national staff and leadership of the Order had been following Wyche’s story. He had been an ardent supporter of KA and had spoken at the Number I’s Leadership Institute, Province Councils, and Emerging Leaders Academy. When asked what his speaking fee would be, he always asked back, “How could I ever charge my brothers?” His message of leadership in his talks resonates very well with undergraduate members even though they’ve never seen him play or coach. All of the young men that attend our programs have always known professional football with a “hurry up” or “no huddle” offense, something Sam is credited with starting and proliferating in the National Football League. As a way to bridge the gap when speaking to our Active Chapter leaders, he passes around the ring he won from Super Bowl XVI (1981) and a handful of other championship rings. Even if the men don’t recognize his name, they recognize his success.

Sam’s heart problems were well known. He had sidelined himself from speaking requests and other activities at one point. He was slowing pretty quickly, and at one point we knew from social media that he was bound to a hospital room. What we didn’t know was just how close Sam got to missing Thanksgiving and Christmas that year. Sam had found his donor heart, was having a successful recovery, but we hadn’t heard much from him except for a couple cable and network news pieces highlighting his new life.

Over the Christmas holiday of 2016, Journal Editor Jesse S. Lyons checked his voicemail while out of state. The following is a transcript of a voicemail that I’ve saved to this day. Brackets added for clarification:

“Hey Jesse, this is Sam Wyche, [then, spelling out his name] W Y C H E. I’m an Iota [initiate], Furman University, 1966.

“I’ve recently had a heart transplant, three months and a week ago. I’m riding my bicycle anywhere from 15–2 miles every day when I go to work out every day, if the weather is nice.

“And I would really appreciate a challenge from KA, through the Journal, to have all the chapters try to register their men as donors of organs and tissue transplants. All they have to do is get a stamp on their driver’s license, or they can go to www. RegisterMe.org, and it goes to all organ recipients throughout the United States. All the states are involved.

“My number is … [XXXXXX-XXXX].

“I don’t know If you saw the piece on NBC Sports before the NFL game on Christmas Day, but they had a nice feature on there about being an organ donor. [It was all about Sam, actually].

“There are quite a few football players and baseball players who [have been]recipients and now there are many who are donors.

“I’m trying to now, as a mission, as I survived it, literally in less than a day, less than an hour. I would like to tell that story and ask all the KAs to become donors. Appreciate it, Jesse. Again, this is Sam, S A M, Wyche, W Y C H E. Furman, Iota ’66.”

This was the message the Order was waiting for from Sam. He was back. He was feeling good. And he was ready to get back in the huddle, or, just skip the huddle and get back to the line of scrimmage.

Sam came back to KA to speak again. This time he visited with the Order’s Executive Council in May 2017, to pitch the organization Donate Life America as an officially sanctioned initiative for the fraternity. The Executive Council unanimously voted in support of encouraging our chapters and members all to sign up as organ and tissue donors. This support would come not only in Sam’s honor, but also as gentlemen we know the Order is predisposed to give back to others—even at life’s very end.

Wyche agreed to attend our 77th Convention in St. Louis in August 2017, to tell his story on KA’s biggest stage and challenge all KAs to save the lives of others. There was a powerful moment when Sam said, “I think it would be a great gesture of today, if we as KA members started a mission to get everyone in KA on that donor list, then challenge your other fraternities at your school to do the same thing.” He asked everyone to raise their hands, all now clad in green Donate Life wristbands, and commit to the challenge. The Executive Council, the Undergraduate Conference, and the Convention all endorsed this initiative again that weekend.

The Order’s Convention wouldn’t be the largest stage for Sam after his transplant. He was thinking bigger. Sam began petitioning the NFL, NCAA, MLB, NBA, and college conferences to play his message and the message of others at their games.

The doctor told Wyche, “on the way home, we want you to call your loved ones, and say goodbye, because you’re not going to live through the night. Your heart is at the very end of its life.”

At 72, the former quarterback and heart transplant recipient was featured and honored with a float ride in the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena earlier this year. Sam rode on the 2018 Donate Life float, along with 16 other transplant recipients from across the country during the January 1 parade. The theme of the float was “Gift of Time.” Sam was actually the fourth South Carolinian to be honored as an organ or tissue recipient in the history of the parade. He wasn’t the only former athlete honored on that very float. Rod Carew, baseball legend, joined him that day. He was the recipient of a heart transplant in 2015. Unlike Sam, Carew learned that his heart came from NFL player Konrad Reuland. Reuland died from a brain aneurysm. He was an organ donor and no doubt saved many lives.

As of yet, Sam has not learned who was his heart donor. It’s up to the donor’s family to share the identity of the donor with the recipient. Sam has written them several times through a clearinghouse to let them know he wants to thank them, but only when they’re ready. They have responded, but only to say that it’s not time yet to connect.

The latest thing Sam has done is to return to the sky. Sam has had a private pilot’s license since 1970. It is a permanent thing, but must be renewed. He is working through that process and is training to recall all the skills and communications techniques back. After more time with his instructor, he’ll be cleared to be back in the sky, solo.

Sam turned 73 in January and is not slowing down. He just wrapped up speaking at KA’s Emerging Leaders Academy this past June. He’s hosting and attending charity events even more now, he says, “Because I know the other end. The children, the families who benefit from those charities, I know how they feel now. I can relate because I’m one of those recipients now.”

There was no Sudden Death in this Overtime. The game of this story is completed and Sam on to a new mission. The game plan now is helping others and saving lives. But for how long? Doctors say a new heart may give an additional 10, 12, 15, 20 years to the recipient. Sam’s response is as exciting as is his future, “Boy I love to hear those double digits!”