Stanford made the right decision: I would not go to New Orleans to play against Tulane in the 1962 football opener.

It was my sophomore year and I didn’t know if a black man had ever played against whites in New Orleans. Teams in the South weren’t integrated then.

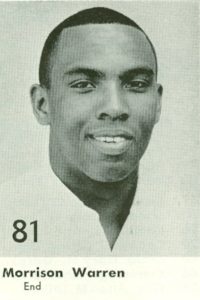

I had a good camp after doing well on the freshmen team. There were a lot of eyes on me, and a lot of expectations, most of which I placed on myself. I couldn’t fail, not as the first recruited black player in Stanford football history.

No hotel in New Orleans would take a team with a black player. Instead, Tulane offered its infirmary. That’s where the team stayed.

At the 11th hour, just before we were about to leave, the coaches pulled me aside and said, “Morrison, we’re going to keep you in Palo Alto. We don’t feel comfortable with what might happen in Louisiana.”

This was only two years after New Orleans schools were desegregated, one year after the Freedom Riders were ambushed and their bus torched in Alabama, and 10 days before 500 U.S. Marshals were called to accompany James Meredith on the first day of classes at the University of Mississippi amidst riots and gunshots.

I knew there were a lot of things happening around us, and we all had a part to play to make a difference. I also believe Stanford did everything in its power to have me play in that game, but it came to the point where Stanford cared for me so much that they didn’t want to take a chance. They did what they had to do. I respected it, and I knew in my heart of hearts that when the team got back, I was going to make a tremendous mark. My day was coming. Maybe I was naïve.

I grew up in Phoenix, Ariz., as the son of Morrison F. Warren. With the Air Force in Germany in World War II, he witnessed the atrocities of the Buchenwald concentration camp. It made such an impact that he made a promise to God. My dad vowed that if he survived the war, he would dedicate his life to building bridges between races. He felt it was imperative that we reach children before the world reaches them first.

After World War II, Morrison F. Warren was a Hall of Fame player at Arizona State.

He went on to study education at Arizona State, and starred at running back. He was the second black player in program history and inducted into its Hall of Fame. In 1948, he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers of the NFL, but hurt his shoulder near the end of training camp, ending his football career. He returned to Arizona and began teaching. He earned his doctorate, became a professor at ASU, joined the Phoenix city council and became a vice mayor of the city, earning the love and respect of the community. He even was president of the Fiesta Bowl.

At South Mountain High School, I earned all-state and All-America honors as a receiver. Even though I didn’t compete in track—I starred in baseball and basketball—I had great speed.

I always wanted to go to Arizona State like my dad, but as my senior season progressed, many schools started talking to me—Arizona State, Arizona, Cal-Berkeley, Harvard, New Mexico, and the Air Force Academy. I even got an invitation from Ole Miss. They didn’t know I was black.

I was the salutatorian of my class and my teachers wanted me to go to an Ivy League school, though I thought Harvard was too far away. I was ready to go to Air Force when I got a call from Stanford coach “Cactus” Jack Curtice, who hadn’t had a winning season since coming from Utah in 1958.

Being recruited

Why was I recruited by Stanford? Probably desperation. Curtice liked to throw the ball and, in 1959, Dick Norman set all kinds of passing records. But in 1960, his top four receivers had graduated, the team had no speed and Stanford sunk to 0-10. There also were indications that Stanford was falling behind other programs, who increasingly began to embrace the black athlete.

To do that, Stanford would have to overcome its reputation. Among blacks, there was a widespread belief that even if they applied, they wouldn’t get in.

Also, consider that Stanford did very little football recruiting in those days and scholarships were offered only on the basis of need.

Curtice must have known his job was on the line and, as a receiver with speed, I could give Stanford exactly what it needed. I hadn’t thought of Stanford before he called, and I wasn’t aware of this reputation. But I knew it was a great school, fairly close to home, and I had a chance to play in the Rose Bowl. I chose Stanford.

There was a problem. My parents were schoolteachers with seven kids and we couldn’t afford it. When I told the coaches, they said, “Give us a couple of days,” and came back with an Alfred P. Sloan academic scholarship. That cemented the deal.

Stanford had two black football players before me. Ernest Houston Johnson enrolled at Stanford in 1891, its first year of existence, and played one season. Ernest was ignored when he first tried to enroll, but Jane Lathrop Stanford interceded.

Tom Williams, a walk-on running back in 1958, was the first in the modern era. This was after Eddie Tucker became the first recruited black athlete in Stanford history, joining the basketball team in 1950. Harry McCalla, a star distance runner, was a year ahead of me.

Was I concerned that they had never recruited a black player? I never thought about it. What I thought at the time was that I had the combination of attributes that a school like Stanford needed. Whomever they selected of color, it was very important for that person to do well in school and be prepared to play well on the field.

I knew I could play and, academically, there never was a question. But I’d be under a microscope. By doing well, I could help pave the way for others. If I didn’t, I’d let people down.

In the late summer of 1961, I got off the bus in Palo Alto at 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning and two players were there to pick me up. One was Steve Thurlow, who would play five years in the NFL as a halfback for the Giants and Redskins. They put me in the front seat and we drove up Palm Drive. I’ll never forget it.

I was one of five blacks in the class of ‘65. There were only two males. The other was from Africa. There were no special programs for orientation or acculturation. No special housing.

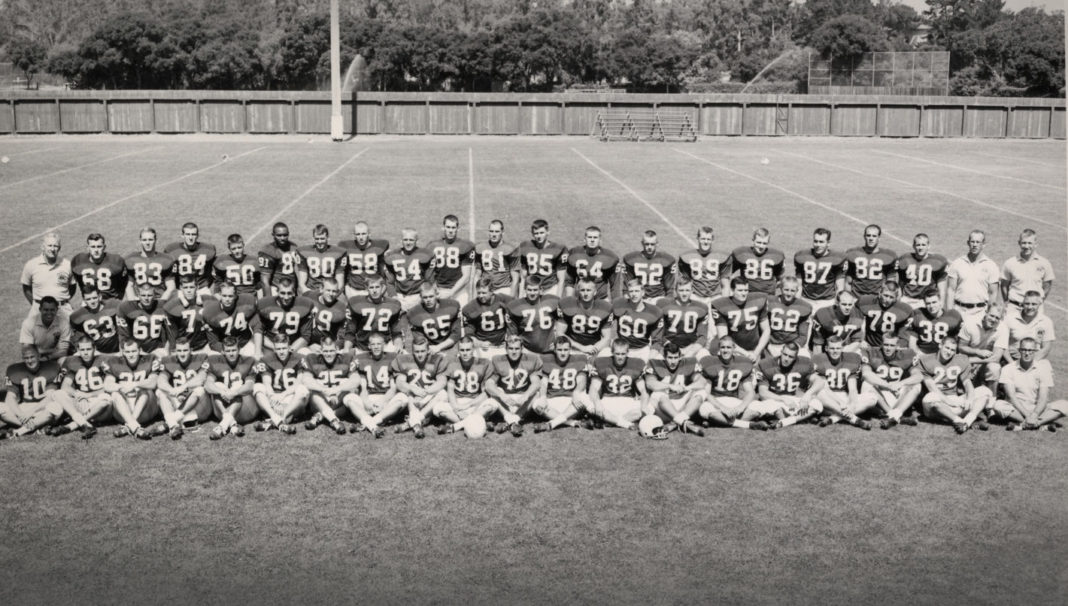

When football camp began, people started coming out to practice to watch me. I felt like the toast of the town. It was strange to think that every day, I was the only person of color to put on a uniform and walk out to that field. For almost every player and coach, this was their first experience with a person of color.

The guys on the team really accepted me. That was no issue. Every Sunday morning, freshman coach Dan Stavely picked me up with a teammate —Dick Ragsdale from Medford, Ore.—and took us to church. Afterward, we would have a little breakfast and he would bring us back to campus. No fanfare. He just wanted to make sure we felt at home.

I had an outstanding freshman year, before freshmen were eligible for varsity. I was 6-feet, 195 pounds and the fastest player on the team. I played halfback, returned kicks, and played a little defense. I was healthy, and the future looked bright.

That began to change during a practice my sophomore year. I was playing defense when John Wilbur, a guard who would play nine seasons in the NFL, pulled and blocked me. I landed hard and dislocated my shoulder. I played a few plays here and there with my shoulder heavily taped, mostly after moving to end, but I was disappointed as hell.

I think Coach Curtice could sense it. Before one game, we had breakfast at Stickney’s across the street from campus. Coach asked me a question about a particular play and what I would do to defend it. I answered correctly. In front of the whole team, he said, “Guys, you all know Morrison well by now. He’s a quiet guy, the first Negro to be brought to the Stanford football team. He’s hurt this season, but he’s come to play. He’s going to end up being one of the greatest players that ever came to this university.”

I almost cried. I was touched by his words, yet frustrated that I couldn’t get on the field to prove myself.

Joining the fraternity

Several of my teammates were members of Delta Tau Delta, a fraternity that did well academically and had a lot of athletes. They extended me an invitation and I pledged my sophomore year. This was not a political statement by anyone, just a guy making friends.

None of us realized there had long been institutional racism built into the national Constitution. Membership qualifications included the phrase, “He must be of the Aryan race.” In 1915, wording was added, “and not of the Black, Malay, Mongolian or Semitic races.”

Though the racial restrictions were removed in 1956, a subtler racist policy was put in place, requiring unanimous acceptance. That meant that if any Delt anywhere, even across the country, had a problem—you were out. And there were many who had a problem with me, though not at Stanford.

I was treated with respect within my chapter, but when a consultant came for a routine visit and discovered I had pledged, he alerted the national office and it went crazy.

Our house started receiving harassing phone calls from other chapters, mostly in the South. Some were downright threatening.

Our chapter took a vote and decided to take a stand. “We want Morrison to be part of our fraternity and we’ll deal with the consequences. You won’t keep us from doing the right thing.”

Stanford offered its support too. If the Fraternity disciplined our chapter, then Stanford would urge schools around the conference to sanction Delt chapters on their campuses.

Our national convention was in Louisiana that year and our representatives were under fire from the moment they landed. Threatened with expulsion, we never backed down.

Our saving grace was U.S. Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark. He participated in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 case that ended segregation in public schools and he was a member of our national board. Though he didn’t have a vote, his presence stood as a symbol of what needed to be done.

In the end, our chapter was censured for ignoring the rules, but it only was a slap on the wrist. We had won. After that, Clark and a Stanford alumnus, George Reppas (Stanford University, 1951), led the effort to change the Delta Constitution, making it safe for others of color to join. I was initiated on March 3, 1963. At Stanford, we were heroes.

Football at Stanford

I didn’t share the same success in football. Curtice was fired after the team went 5-5 in 1962 and John Ralston was hired from Utah State.

Coach Ralston developed a relationship with Admissions Director Rick Snyder, helping convince his office to look at potential rather than solely academic achievement. Soon, Stanford began to diversify its student body. Two years after I arrived, Stanford had six black football players: Roger Clay, John Guillory, Dave Lewis, Ron Miller, Dale Rubin and Al Wilburn.

The influx turned Stanford football around. The great Bill Walsh, an assistant from 1963-65, was largely responsible for starting the pipeline through his recruiting. If that hadn’t happened, Stanford probably never would have won Rose Bowls in 1971 and 1972.

Things were going great. Coach Ralston and Assistant Coach Rod Rust were very fair to me. I didn’t even think about my shoulder anymore. Coach Rust moved me to outside linebacker and told me I was going to start against UCLA, in our third game of the season. I felt like I finally was over the hump.

Practice late that week was supposed to be something like a walk-through, not a full scrimmage. The offense ran an end sweep, but instead of the lineman just coming in and blocking me a little bit, the guy hits me low. I tear my ACL.

In those days, if you hurt your knee, it ended your career. I didn’t know how bad the injury was. On Sunday, the day after the 10-9 loss to UCLA, I hobbled and limped to the team room to watch film of the game. The kid who ended up playing my position, Ed Ptacek, had a pretty good game. I remember the coaches saying, “Good job, Ptacek.”

That motivated me even more to get back on the field. So, on Monday, I practiced with the guys who didn’t play in the game. But almost as soon as I got on the field, I collapsed. My knee gave out. I had surgery and never played again.

I was devastated. I asked, “Why me, Lord? I’m just trying to come here and do something special.” I realized even then that when people would look back, they wouldn’t know about Morrison Warren. I would never become the great player I thought I would be. It was nothing I could control.

Through all that, I never lost my faith in Stanford. I actively recruited Art Harris, who would become one of Stanford basketball’s all-time greats. I told Gene Washington that Stanford was a wonderful university and that he would get every opportunity to play, a great education, and could be someone special here. And he was.

Life after football

I quietly graduated with a degree in economics and a minor in math. But football was a big disappointment. The thought that I failed physically continued to haunt me. My knee never was the same, but I refused to believe it.

I entered law school at University of Arizona, but I couldn’t overcome a sense of unfulfillment, and I left after a year to join the Marine Corps. To most people, it didn’t make any sense, especially during the Vietnam War. My dad would tell us, “This country respects warriors. If there’s ever a need to go into the military, you should do it.”

Somehow, I passed the physical and got through Officer Candidates School in Quantico, Va. I trained at Camp Pendleton near San Diego and was sent to Vietnam in 1967 with the Amtracks, the Assault Amphibious Vehicle Battalion.

But not long after arriving in Vietnam, I injured my knee again, and I was discharged. The injury may have saved my life, though I wasn’t in any mood to believe it at the time. All I knew was that I was back home, again a failure. I stared at the scars on both sides of my knee and realized that, somehow, I needed to move on. I was ready to start my life.

I decided to go back to law school, but needed money first. So, I returned to Valley National Bank in Phoenix, where I worked one summer. I ended up staying 42 years. In April 2015, I retired as senior vice president of a company that evolved into Bank One and JPMorgan Chase.

I often think back to my grandfather, Fred Warren. In 1925, he came from Marlin, Texas, with a wife and six kids. He worked at a hotel for 37 years without missing a day. He never went to college, but always preached the importance of education.

I think of my maternal grandmother, Ramona Padilla, who crossed the border from Mexico. She never went to school, but she was a math genius. She always preached: “Do the best you can. Always leave something better than you find it. Give more than you take. And when something special happens to you, thank the Lord.”

These people, who had virtually no education, produced descendants who would earn dozens of college degrees, from some of the world’s greatest universities—Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Northwestern, and the University of Chicago.

If you ask people in Arizona, the Warrens are known to be hard-working, great students and very good athletes. My baby brother, Kevin, the COO of the Minnesota Vikings, is the highest-ranking black executive of an NFL team. My sons and daughters have been successful and made me proud. My granddaughter, Sarah Warren, is a Big Ten All-Academic soccer player at Illinois and a potential Olympic speed skater.

The Warrens are a melting pot of blacks, Mexicans, Native Americans and whites. My family didn’t mess with anybody and nobody messed with them. We’re not intimidated by obstacles and we never use them as excuses.

When I came to Stanford, I thought I would change the world and Stanford did everything it could for me to live up to that dream. It invested in me because of the promise I showed—and that degree has paid off exponentially in creating standards for my children and grandchildren to live out their own dreams without limitations.

I’m 74 now and my memories of Stanford are some of the fondest I have in life. I think about all my brothers in Delta Tau Delta who chose to take a stand for me. I think about the university. I owe so much to Stanford. It’s special in my heart.

Our family came from nothing, but that never stopped us. In a way, our story is an American story, full of hopes, dreams and promises. That promise still exists. My family believes in it. It always has. And, thanks to Stanford, so do I. I’ve lived it.

My American Story is reprinted with permission from Stanford Athletics. Learn more about how Delta Tau Delta’s International President Justice Tom C. Clark (University of Texas, 1922) addressed inclusive of membership language and spearheaded the effort to overhaul the Fraternity Constitution and Bylaws in 1968, in the summer 2018 issue of the Fraternity’s magazine.