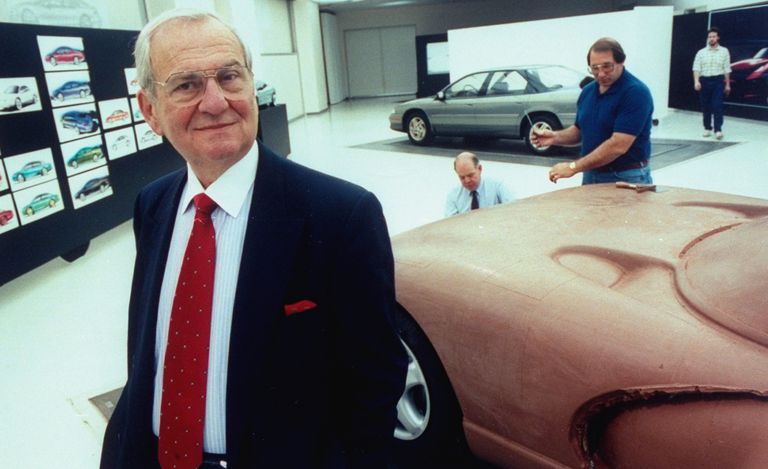

Lee Iacocca was a salesman. He sold Fords, he sold Chryslers, he sold Chrysler Corporation, and he sold himself. He was the face of American capitalism who, in the great tradition of American capitalism, put the touch on the American government to keep his enterprise going. He was a celebrity CEO when CEOs weren’t supposed to be celebrities. The Theta Chi brother passed away on July 3 at age 94.

“You can have brilliant ideas,” he wrote in his best-selling Iacocca: An Autobiography, “but if you can’t get them across, your brains won’t get you anywhere.” Lido Anthony Iacocca could most certainly get an idea across.

He was born in 1924 in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to Nicola Iacocca and his wife, the former Antoinette Perrotta. Allentown was a thriving steel town then, mostly Pennsylvania Dutch but the sort of place where Italian immigrants could find a community to support them and an opportunity to build a life. Nicola Iacocca found his niche running a hot-dog restaurant called the Orpheum Wiener House.

“My father always drilled two things into me,” Lee related in his autobiography: “Never get into a capital-intensive business, because the bankers will end up owning you. (I should have paid more attention to this particular piece of advice!) And when times are tough, be in the food business, because no matter how bad things get, people still have to eat. The Orpheum Wiener House stayed afloat all through the Great Depression.”

After graduating from Allentown High School, Iacocca earned a degree in industrial engineering from nearby Lehigh University and afterward was hired by Ford as an engineer. But instead of going to work for Ford right away, Iacocca won a Wallace Memorial Fellowship to study engineering at Princeton University for a year and earn a master’s degree. So, it was off to New Jersey first. He finally went to work in Dearborn as a student engineer in August 1946.

“The day I arrived, they had me designing a clutch spring,” he wrote. “It had taken me an entire day to make a detailed drawing of it, and I said to myself: ‘What on earth am I doing? Is this how I want to be spending the rest of my life?’ ” He wanted to get into sales.

Starting in the Chester, Pennsylvania, regional sales office, Iacocca was soon a rising star at Ford. By 1949, he was a zone manager out of Wilkes-Barre, visiting dealers and learning the business at the retail level. “Learning the skills of salesmanship takes time and effort,” he wrote in his autobiography. “You have to practice them over and over again until they become second nature.”

Ford had decided that it would sell the 1956 Fords using safety as a hook despite the fact that, at the time, customers couldn’t have cared less about safety, and Ford was facing a sales disaster. That opened the door for Iacocca’s first legendary sales push. Working out of Philadelphia, he conjured up the idea that any customer should be able to buy a new ’56 Ford for 20 percent down and $56 a month for three years. His “56 for ’56” was an instant success, and it got him noticed back at Ford’s mother ship.

Also in 1956, he married Mary McLeary, who had been a receptionist at the Ford plant in Chester. They’d have two daughters together before she passed away from complications of diabetes in 1983. He would have two subsequent marriages that didn’t stick.

Ford pushed the “56 for ’56” campaign nationally, and by 1960 Iacocca had been named vice president and general manager of the Ford Division. Soon after that, his product instincts kicked in with vehicles like the original Mustang—a rebodied Falcon with sex appeal. He had an almost unerring sense of what would sell and how to sell it. By 1967 he was an executive vice president and conjuring up vehicles such as the 1969 Lincoln Continental Mark III.

Iacocca wasn’t just an automotive icon by the mid-Eighties but a big presence in the culture at large. Some urged him to run for president of the United States, Johnny Carson cracked jokes about him on the Tonight Show, and he did a guest cameo on Miami Vice as “Parks Commissioner Lido.” His 1984 autobiography, co-written with William Novak, was an instant best-seller and so popular that it was the New York Times’s best-selling nonfiction hardcover book in both 1984 and 1985 and sold almost 2.6 million copies before being issued in paperback. In a sense, he elevated the role of corporate CEO into that of celebrity.

Lee Iacocca retired from Chrysler in 1992 and would go on to lead other projects like the restoration of the Statue of Liberty. He even teamed up with Kirk Kerkorian in 1995 to take a run at once again controlling Chrysler (it didn’t work).