2018 Chi Psi Convention Banquet Speaker and 22-23 O’Brien Fellow Lee Hawkins, Chi Psi University of Wisconsin ’93, a special correspondent for American Public Media, recently shared a story about how his third grade substitute teacher transformed his life.

How one Black teacher on one day helped me — a Black kid in a mostly white school — feel less alone

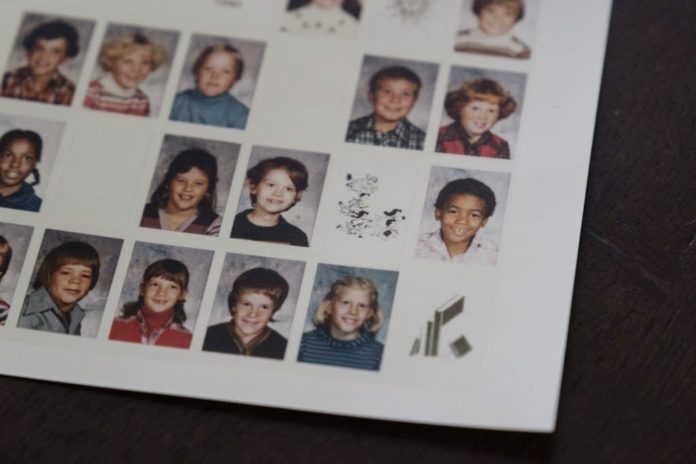

On even the most ordinary days, teachers can impact the lives of their students in extraordinary ways. I learned that on one morning in 1979, as a third grader and one of the few Black kids at Weaver Elementary School in Maplewood.

That day, I was swarmed at the coat rack by a cluster of hyped-up, freckled and rosy-faced classmates who greeted me by yelling, “Your dad is here! Your dad’s gonna be our teacher today! Is that your dad?”

The year was already a disaster. A small few of my tiny classmates were calling me the n-word more than they called me by my actual name, prompting me to respond with my fists. In fact, my teacher had sent me to the principal’s office several times and called my parents to complain about my behavior — including one time for punching kids who had a fascination with touching my short afro and would follow up by saying, “Ewww, you have grease in your hair!”

Sometimes, my teacher’s in-class punishment for some errant students was placing our desks in the corner facing the wall, surrounded by a foldable wooden partition that felt like a little pop-up jail for budding juvenile delinquents. Much worse, was the belt whipping that followed at home. Like many parents from the ‘70s and ‘80s, my folks considered the belt to be the highest expression of love and protection that a Black parent could show. They believed it was a way to scare me — as a third grader and a Black male — into learning how to self-govern my behavior to keep myself away from street violence, the drug trade or gangs, or deadly encounters with the police.

My mother worried that bad reports from teachers was the beginning of what we now call the “school to prison pipeline.” Considering the statistical reality that Black students across America are more likely than their white peers to be suspended, expelled or arrested for the same kind of conduct, I now know that, in fearing that possibility, she wasn’t entirely wrong.

When my classmates greeted me, I was immediately overcome with worry, thinking that my father came to the school to do what my mother often promised she’d do if I didn’t straighten up: Give me an ol’ fashioned, American Southern Baptist belt whipping in front of all of my white classmates.

I bravely took off my red snowmobile suit and silver moon boots and walked into the room. And then, there he was, my so-called “dad,” looking down at all our innocent faces. Thankfully, he carried a welcoming grin and a kindly introduction. “Hello boys and girls, my name is Mr. Bridgeman. Mrs. Blumer is out, and I will be substituting for her today.”