The 1970s were a tumultuous time for the American college fraternity. With membership waning and many questioning the long-term benefit of fraternal organizations, Pi Kappa Phi Executive Director Durward W. Owen paused to consider the future.

If Pi Kappa Phi was going to remain relevant in the years ahead, what would it take? Durward ultimately determined that their students needed an opportunity to directly engage in service to others. While the concept seems obvious by modern standards, the proposition was unheard of at the time.

Through his work with the North Carolina Governor’s Advocacy Council for Children and Youth, as well as the Western Carolina Center, Durward learned about the challenges facing people with disabilities. There was no particular personal attachment to this cause, as he would later share; instead, it was a recognition of the need to advocate for this underserved population coupled with a desire to create hands-on service opportunities for the members of Pi Kappa Phi that ultimately led them to 40 years of service advocating for the abilities of all people.

In reviewing the proposal for a “school of advocacy” within Pi Kappa Phi aimed at raising awareness about the disability community, John Wilson (Emory) aptly challenged the initial concept. While advocacy was important, he noted, even more critical was a need to give every brother of Pi Kappa Phi the opportunity to directly contribute to service to others — the fraternity needed to offer something hand-ons to our members across the country.

And so began Durward’s friendship with Thomas Hart Sayre [later an alumnus initiate at UNC – Chapel Hill], a local artist working at the Western Carolina Center. By trade, Sayre was a sculptor. A graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he believed that people with disabilities could achieve far more than society expected, both personally and developmentally, if they were better accommodated at an early age.

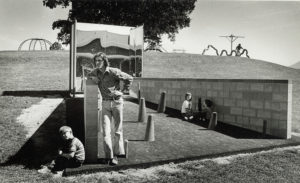

Those who knew Sayre from his childhood considered him brilliant — a person with a propensity for creativity, empathy and independence. As a young adult, that brilliance shined forth in his art — the vehicle through which he designed environments better suited to the needs of people with disabilities. The director of the Western Carolina Center hired Sayre to create a shared, outdoor playground for the children with disabilities they served. Since the budget for the state-run healthcare facility did not include a line item for a sculptor, Sayre took on the title of janitor and set to work.

Recalling their first meeting, Durward described Sayre as a caring, intelligent and sensitive person. While the two may have come from different backgrounds and different life experiences, they shared a common goal: To better the lives of others and the world around them through their work. As their relationship and friendship grew, Pi Kappa Phi began to fund some of Sayre’s work. And so began the early foundations of Project P.U.S.H.

Originally called Play Units for the Severely Handicapped (P.U.S.H.) in recognition of Sayre’s endeavors, this homegrown service project became an opportunity for brothers across the country to directly impact local communities and to show a side of fraternity that society saw far too infrequently — a fraternity that was strong enough to care and to defy the stereotype.

The 36th Supreme Chapter overwhelmingly adopted P.U.S.H. as the national service project of Pi Kappa Phi in 1977 and encouraged our chapters to raise funds to support the installation of play units benefiting people with disabilities across the country. That support allowed the play units designed by Sayre to be installed from Pennsylvania to Idaho within just a few years; and so the movement grew, from an idea born in the mountains of North Carolina to a truly national cause for the brothers of Pi Kappa Phi.

As chapters continued to raise funds and awareness for the work of this fledgling non-profit, a recent graduate of the chapter at Stetson embarked on a fundraising journey for P.U.S.H. in the summer of 1987 after graduating law school. Asking friends and family to sponsor each mile of his trip from Oregon to Virginia, Bruce Rogers decided to cycle across the country in support of people with disabilities, raising $2,000 as he traveled 3,000 miles over the next three months.

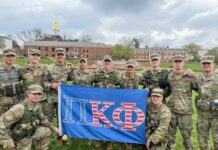

That initial adventure inspired student Jim Karlovec (Bowling Green) to begin plans for a ride and Ken Kaiser (Bowling Green) working then on the P.U.S.H. staff, to create the first summer cycling event in 1988. With a vision often described as too lofty, Kaiser and recent-graduate T.J. Sullivan (Indiana) envisioned the opportunity: Brothers from across the country cycling, volunteering, and working with community partners serving people with disabilities. That summer, “P.U.S.H. America” set off with 25 brothers from across the U.S. and raised over $50,000.

“the themes of teamwork, friendship and brotherhood that helped us succeed in 1988 have carried over from year-to-year.”

The team was organized by Jim Karlovec; and from the beginning, their trip was always about more than just fundraising. Dozens of stops were scheduled along the route allowing the cyclists to educate community members, city councils and other non-profits about people with disabilities. The trip was later described as “a journey of hope” — a moniker that ultimately came to describe our three cross-country cycling routes each summer.

In addition to raising funds and awareness through a national cycling event, the P.U.S.H. staff also considered how to truly weave Wilson’s original vision—the desire to give every brother of Pi Kappa Phi a hands-on service experience—into the organization’s work. From east to west, our service project remained committed to not just fundraising and awareness, but to directly impacting the communities in which our members lived.

In 1989, Holy Angels—a non-profit devoted to the full-time care of adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Belmont, N.C.—hosted the first Give-A-PUSH Weekend. What started as P.U.S.H. Executive Director Ken Kaiser’s vision for bringing student members from across the country together to construct needed equipment and fix worn facilities eventually grew into “Push Place,” a part of the Holy Angels camp that brought smiles to the people they served for years to come.

As P.U.SH. grew from a focus on fundraising and awareness to national cycling and construction events, so too grew the organization’s national presence. Along the 1989 Journey of Hope route, cities and states routinely declared “P.U.S.H. America Day,” and that year’s arrival in Washington, D.C. — the first in our nation’s capital — was attended by numerous Senators. Each trip also provided an uncommon opportunity for students to build upon the friendships developed with organizations and people with disabilities across the country by men before them. From one team to the next, those shared experiences became central to the organization we know today.

From Give-A-PUSH Weekend, we expanded to PUSH Camp, an alternative break program launched in 1991 at the Clemson Outdoor Lab — an organization with whom The Ability Experience still partners today — allowing our brothers to spend their spring break serving others. From PUSH Camp, the idea of directly benefiting the disability community went local with AccessABILITY, a program created in 1994 to build wheelchair ramps and improve access to the homes of people with disabilities across the country.

In 1992, the South route was added to what became known as the Journey of Hope in 1995, the same year P.U.S.H. formally adopted the name PUSH America, reflecting a mission far broader than constructing accessible play units. By 1997 — the 10th anniversary of Bruce Roger’s first journey across the country — nearly 400 brothers had cycled more than 60,000 miles and raised over $2 million for people of all abilities. “Although the trip has changed drastically in 10 years,” wrote Eric Almquist (Iowa State) a cyclist on the first Journey of Hope team, “the themes of teamwork, friendship and brotherhood that helped us succeed in 1988 have carried over from year-to-year.”

That same year, the organization once again changed its name, this time using “Push America” to further distinguish our modern work from the original cause of constructing play units. The founding principles, however, remain a constant in the story of what we know today as The Ability Experience: An opportunity for the men of Pi Kappa Phi to develop themselves through service to others and the betterment of the world around them.

Gear Up Florida was added in 1997 as one of our summer event opportunities, providing brothers with a chance to have shared experiences and build lasting friendships with people with disabilities across the state of Florida as they cycle for two weeks from Miami to Tallahassee.

As our fraternity continues to grow, so too do the uncommon opportunities provided by The Ability Experience. From the creation of Build America, an annual team of brothers traveling the country promoting accessible recreation for people with disabilities, in 2002 to the addition of the TransAmerica route on the Journey of Hope in 2005 to the launch of Ability Experience Challenges to further expand not only our mission and impact but access to our events for students and alumni alike, our commitment to servant leadership has always evolved with the world around us. In 2014, Push America evolved once again to become The Ability Experience, a succinct representation of our commitment to the abilities of all people and to the shared, hands-on experiences that make this organization truly unique in the interfraternal world.

Since Pi Kappa Phi founded The Ability Experience 40 years ago, they have raised more than $25 million dollars to benefit people with disabilities; but the impact of this organization is far greater than fundraisers and grants.

Week after week, students across the country serve others through local partnerships with organizations serving people with disabilities. Year after year, their students have shared experiences with people with disabilities through national and regional events that make them better citizens of the world. Moment after moment, they learn from those around them, both brothers and the members of the community they are called to serve.

Since 1977, they have learned the importance of people-first language and advocated for the end of the R-word, not because political correctness requires it because respect for others is central to the work of The Ability Experience. They have learned to be empathetic and to value the contributions of all people. And over the arch of this incredible organization’s history, they have learned to become servant leaders—in precept and action—as they strive to better the world around us.